Field and counter-field by Maria do Mar Fazenda

By Maria do Mar Fazenda

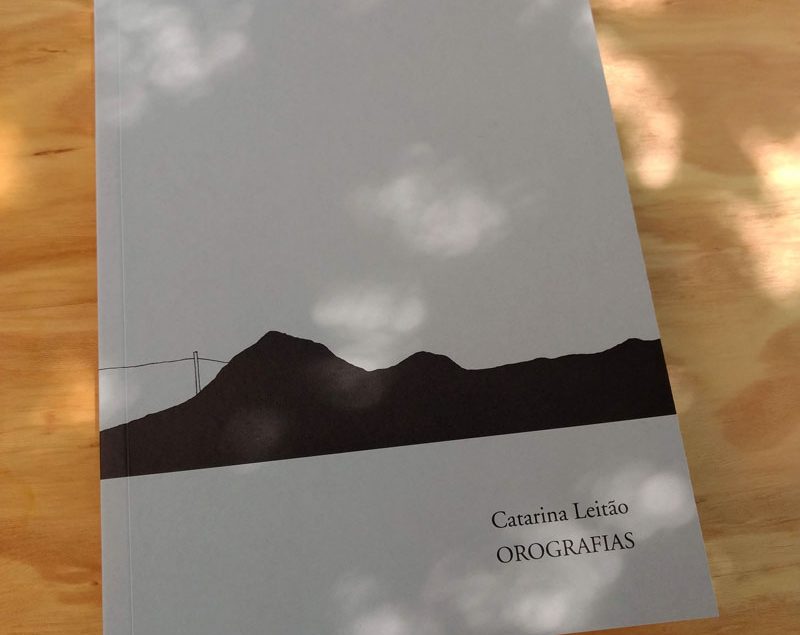

in Catarina Leitão | Orografias, Giefarte/Documenta, Lisboa, 2019.

It was a gray, rainy day when I drove from Lisbon for a studio visit at Catarina Leitão’s (b. 1970, Stuttgart), who has been living in the countryside for some time now. I decided against using the GPS, and instead followed the instructions Catarina had emailed me to navigate roads I had never ventured on before. I felt like following the landscape, not its impression on the road or its reproduction in the directions I had been given: turn right, now left, second exit on the roundabout, exit X, kilometer Y, etc. I got lost. Perhaps I got lost because I was gazing too attentively at the Unstable Landscape (title of a series from 2017) unfolding in front of me as I drove up and down, alternating between paved and dirt roads, curving here and there through cultivated lands, passing by walled houses, unfinished constructions, roadworks, trees and reed beds, traffic signs and lamp posts…

Catarina’s instructions not only described and mapped (in words) a certain route, but they also evoked — as I would later understand, seeing the pieces she had been working on — the drawings (better still, the thought processes that trigger her drawing) of the series that would later receive the name Orographies.

There’s a football field just before the village, on the right. Right after that, the road curves. Turn right after the curve. You’ll see construction works, they’re building a sidewalk in front of some orchards. There’s a high voltage post by the road, and white houses on the top of the hill. Go up the dirt road and continue till you get to the house with a blue strip… (excerpt from an email Catarina sent me, a few days before my visit. The highlights are hers.)

It is possible I got lost because the instructions were too detailed: they described the before and the after of a given morphology, explaining what I would see in front and behind a mountain, singling out trees on the side of the road, etc. They could be the description of a map, the graphic representation of a totalizing vision: a bird’s-eye view. At that moment, I was baffled with the conflict between landscape and written description. The directions corresponded to a terrestrial perspective, but it was also one that was observing (and mapping) things that were beyond its field of view.

This capacity to see beyond the abilities of the photographic gaze, for example, is one of the characteristics of scientific drawing, which is not circumscribed to what the eye sees from a given point of view, but is able to see (and draw) beyond the limits of perspective. The scientific drawing of a fish, for example, can give extra detail to its gills, unfolding them and allowing us to see inside, reproducing in the drawing something that does not correspond to their natural state. Notwithstanding, these “untruths” are drawn to favor a scientific and pedagogic truth: to study, to analyze, to reveal. Just like in maps, the rules of cartography present us a scientific truth that is revealed through omissions and small incongruences between drawing and text (the labels), the scales, orientation and projections. Even its support, paper, gets to play a role in this game of occultation and revelation: its size, how it folds, its transparency, etc.

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the Orographies (from the Greek óros, mountain, and graphein, to write) in these drawings do not correspond or describe any given territory, and certainly not the one where I managed to get lost. Drawing can reveal what is hidden, but is also capable of creating new things, and it can also hide what it makes possible for us to see.

These landscapes are fictions, even though they are composed of real things: a horizon, things above and below the ground, a ridge, a chasm, monocultures, sediments, energy discharging on the land, etc. The drawing of these landscapes considers various geographic, morphological, meteorological preponderances while integrating ecological, economic, political, real, concrete and contemporary signals. Conceptually, the landscape Catarina Leitão describes in her Orographies can be associated with the notion of third landscape, coined by the architect, gardener, botanist, agronomist and entomologist Gilles Clément in his essay Le Manifeste du Tiers-Paysage.

The Third Landscape – an undetermined fragment of the Planetary Garden – designates the sum of the space left over by man to landscape evolution – to nature alone. Included in this category are left behind (délaissé) urban or rural sites, transitional spaces, neglected land (friches), swamps, moors, peat bogs, but also roadsides, shores, railroad embankments, etc. To these unattended areas can be added space set aside, reserves in themselves: inaccessible places, mountain summits, non-cultivatable areas, deserts; institutional reserves: national parks, regional parks, nature reserves.

Compared to the territories submitted to the control and exploitation by man, the Third Landscape forms a privileged area of receptivity to biological diversity. Cities, farms and forestry holdings, sites devoted to industry, tourism, human activity, areas of control and decision permit diversity and, at times, totally exclude it. The variety of species in a field, cultivated land, or managed forest is low in comparison to that of a neighboring «unattended» space…

From this point of view, the Third Landscape can be considered as the genetic reservoir of the planet, the space of the future…

Let us go back to the directions Catarina gave me. Their richness in detail is indicative of an attentiveness to a changing landscape, either by the action of the elements or by human hand. Her practice of drawing also draws from the tension between study and imaginary, natural and artificial, rule and invention.

In order to produce this assiduous observation of the real while departing from it, one needs to be, concurrently, on-field and off-field. It seems to me that it was precisely in the pursuit of this notion that Catarina Leitão created the piece Portable Studio in 2014, a working space that allows for overlapping perspectives. Using this studio, the artist can work amidst nature, like Cézanne in the last years of his life, trading his studio for the open air so that he could paint the Mont Sainte-Victoire. In the case of Cézanne, this became a daily activity, compulsive, obsessive and immersive, void of critical distance. Even if she points towards the same movement outwards (or chooses to place herself in the boundary between internal and external space, which is an apt description for her current studio), Catarina Leitão’s practice is opposite to Cézanne’s. The painter used reality to produce the unreal, a process synthetized in the moment where his painting of the reliefs of a mountain is no different from the painting of the pleats of a table-cloth in a still-life.

The reliefs in these Orographies, much like the species dissected in her series of drawings Systema Naturæ (2012), are not reproductions of any recognizable mountain range or of a particular botanical species, even if the way they are drawn, using rules that we recognize as “scientific”, confers them some level of truth and critical reality. Besides this duality between real and invention, there is yet another simultaneity at play. On the one hand, these landscapes expand on a conversation with a wider landscape — Catarina Leitão’s body of work — and, on the other hand, they are informed by her experience of certain territories: Catarina has lived in Manhattan, in downtown Lisbon, and this series of drawings owes its inception to an artistic residency in the island of Madeira. An example of this “living heuristics” lies in the atmospheric conditions (what is above the horizon) depicted in the triptych Orographies #001, but also in some of the smaller drawings in this series: the sky seems to be heavy and pregnant with moisture, a common phenomenon in Madeira. In the preface to his Portuguese translation of Goethe’s Cloud Poems in Honor of Luke Howard, João Barrento describes this relationship between practice and observation, analysis and drawing:

Goethe’s writing and study of the clouds will always reveal, through Howard, two complementary facets: one empirical (but not yet scientific: corresponding to observation and description, also through drawing), and other symbolic (but not properly philosophical, at least not in terms of systemic conceptualization: corresponding to interpretation, sometimes in works of poetry), under two fundamental rules of his thinking: polarity (systole-diastole, attraction-repulsion, active-passive) and potentiation or elevation to a superior power (from the phenomenon to the idea, from the physical to the spiritual, from the low stratus to the high cirrus…).

The conjugation of heuristics with a live perspective of things seems to be the method behind these field notes, and an apt description of the artistic research and practice of Catarina Leitão, focusing on the landscape as a confluence of forces that can be physical, human or technological. Often, her works take on the format of books, artist’s books or sculptures (or expanded Drawing), that stage a discourse on a certain form. The format of the drawings in the series Orographies, as the title suggests, is that of a map or chart: open and comprehensible. The views of this field are multiplied in different cuts, perspectives and sections of terrain, as well as in fragments that are emphasized and reproduced in other scales. Often, the description of the structure or of the composition of a relief is organized in pages drawn on the plane of the paper. Later, in a second moment, already back in the studio a new perspective is found on the territory that is really being defined: drawing.

Coined by Robert Smithson, the pair Site/Non-site suggests an exploration of the dialectics between outdoor and studio practice, the experience and movement that shaped the relationship between his work and landscape. In an interview he gave in 1969, Smithson proposed a new interpretation for the work by Cézanne, which he believed had been misrepresented by the Cubists, who had reduced it to a strictly formalist play. Smithson called for the need to recover the physical references in Cézanne’s work, and its strong connection to certain places in Provence, especially to the Mont Sainte-Victoire. I take pleasure in imagining that this throwback to Cézanne by Smithson emerged in the context of his landscape intervention Asphalt Rundown, in 1969, in Italy. I identify the same type of affective relationship with the territory, as well as a common desire to rescue it from the passage of time. In the case of Cézanne, it is a rescue from an archaic time: “Look at this mountain, it was once fire.” Smithson and Catarina Leitão engage with this temporality, which has now been hijacked by capitalist time. In these notes from the field and from the counter-field, one might find the drawing (the presentation, the exploration and the description) of a counter-time.

Maria do Mar Fazenda

Lisboa and Arrábida, April 2019